As interest in alternative investments grows high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), RIAs, wealth managers, and consultants are increasingly being asked to evaluate and explain investment opportunities in private equity and private credit. For advisors deeply familiar with public markets, this represents a new learning curve, one that demands not just theoretical understanding, but practical fluency in how these alternative investments vehicles actually operate.

Below we’ll outline the core mechanics behind private equity and private credit investing, including fund structures, cash flow dynamics, return drivers, and the investor’s role within the process. By demystifying the operational backbone of alternative investments, we aim to equip advisors with the tools to assess opportunities and guide client expectations with clarity.

The GP/LP Structure

Nearly all institutional private equity (PE) and private credit (PC) funds are organized as limited partnerships. In this structure, the General Partner (GP) is the fund manager responsible for sourcing deals, making investments, managing the portfolio, and executing exits. The Limited Partners (LPs) which include pensions, endowments, family offices, and increasingly, HNWIs via feeder funds or platforms commit capital to the fund but do not engage in day-to-day management.

When an advisor’s client invests in a private fund, they typically do so as an LP. This role is passive in the operational sense, but deeply strategic in portfolio planning and commitment management.

Capital Commitments and the Fund Lifecycle

Unlike mutual funds or ETFs, where the full investment is deployed immediately, private funds operate on a “committed capital” model. Investors commit a specific amount (e.g., $1 million), but only fund that commitment over time through capital calls, also known as drawdowns.

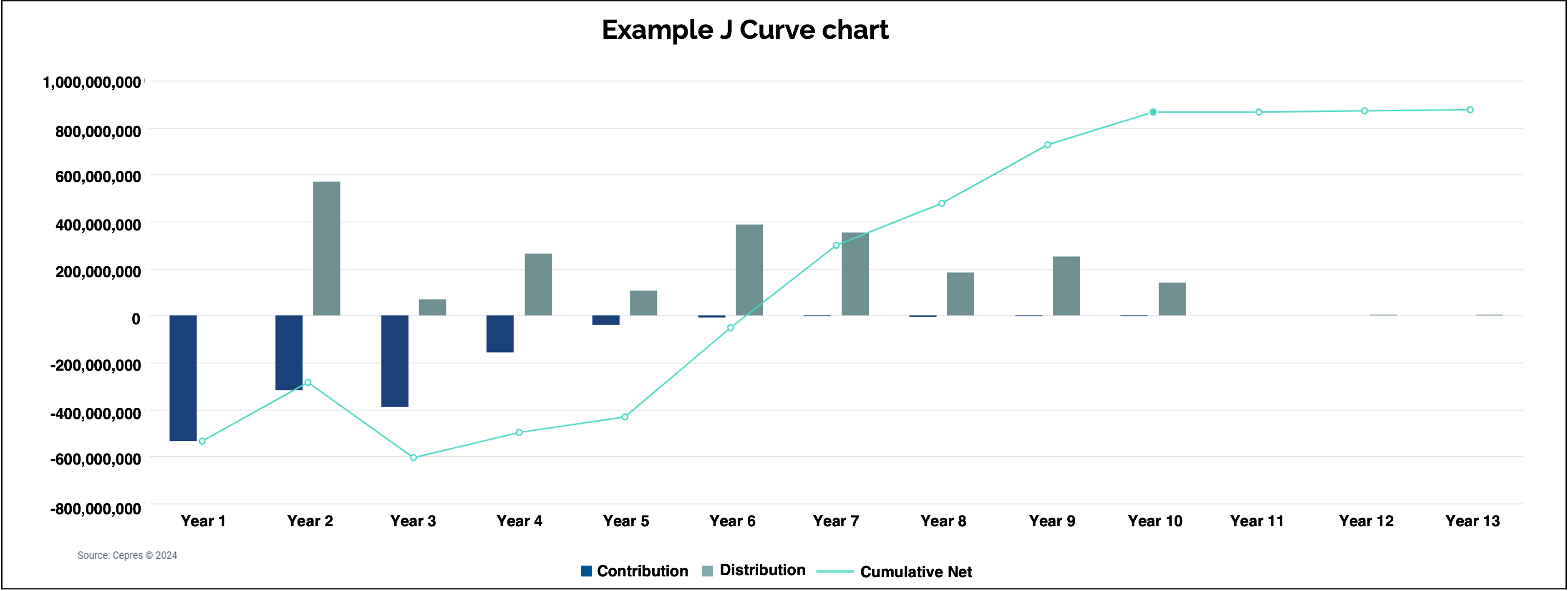

The typical fund lifecycle spans 8–12 years and includes:

Fundraising Period (0–1 years): The GP raises capital from LPs, who sign subscription documents and legally commit to the fund.

Investment Period (1–5 years): The GP calls capital as deals are sourced. This is when the bulk of investments are made.

Hold/Value Creation Period (3–7 years): Portfolio companies are actively managed. In private equity, this might involve operational improvements, M&A, or governance changes. In private credit, it involves monitoring credit quality and receiving interest payments.

Harvesting Period (5–10+ years): Assets are exited via sales, IPOs, or recapitalizations. Distributions are made to LPs as proceeds are realized.

Understanding this timeline is critical for advisors when setting client expectations about liquidity, return pacing, and the “J-curve”, a pattern where returns are negative in the early years due to fees and initial capital outflows, but rise as investments mature and exit.

Distributions and Return Mechanics

Returns in alternative investments are typically realized through distributions, the return of capital and profits to LPs. These are not continuous dividends, but periodic, event-driven cash flows triggered by investment exits or loan repayments.

In private equity, returns come from selling portfolio companies at a gain. Value creation may come from operational improvements, multiple expansion, financial engineering, or strategic synergies. The performance is often highly dependent on the GP’s skill in sourcing and managing deals.

In private credit, returns are generated through interest payments (often floating rate), fees, and principal repayment. Because credit investments rank higher in the capital structure and typically carry collateral, private credit is often seen as a lower-volatility alternative to equity, though it carries its own risks related to borrower creditworthiness and liquidity.

Fees, Carried Interest, and Alignment

Private fund economics also differ from traditional funds. GPs charge both a management fee (typically 1.5%–2% annually on committed or invested capital) and carried interest (usually 20% of profits above a performance hurdle, such as an 8% internal rate of return).

This “2 and 20” model aligns incentives between LPs and GPs, but advisors must understand how these fees affect net returns, and how they vary by strategy and manager. Some funds offer preferential terms or fee breaks for early or large commitments.

Evaluating Risk and Return Drivers

In public markets, performance tends to cluster near benchmark indices. In alternative investments, however, manager selection is critical. The dispersion between top- and bottom-quartile private equity managers can be over 1,000 basis points meaning the right manager can make or break portfolio success.

Advisors must assess:

Strategy fit (buyout vs. growth vs. credit)

GP track record and team continuity

Fund terms and transparency

Alignment of interest between GP and LP

Historical drawdown and distribution patterns

This underscores the importance of high-quality data, benchmarking tools, and diligence platforms that allow advisors to move beyond marketing decks and gain real insights into fund performance.

Final Thoughts

To participate meaningfully in alternative investments, advisors need more than enthusiasm they need a clear operational understanding of how capital is committed, deployed, and returned. The GP/LP structure, the lifecycle of a fund, and the unique return drivers of equity and credit strategies all influence how alternative investments behave within a client’s broader portfolio.

By grasping these mechanics, RIAs, wealth managers, and consultants can become credible stewards of private capital access offering sophisticated guidance that bridges the growing gap between client curiosity and advisor confidence.

Want to know more? Learn how CEPRES Market Intelligence can help you maximize private equity returns, mitigate risks, and uncover hidden portfolio opportunities.

Read the next article in the series Risk, Liquidity, and the Myths of Alternative Investing